Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is a doubly landlocked Central Asian Sovereign state. It is a secular, unitary constitutional republic, comprising 12 provinces, one autonomous republic, and a capital city. Uzbekistan is bordered by five landlocked countries: Kazakhstan to the north; Kyrgyzstan to the northeast; Tajikistan to the southeast; Afghanistan to the south; and Turkmenistan to the southwest.

In ancient times, Uzbekistan was part of the Iranian-speaking region of Transoxiana. The first recorded settlers were Eastern Iranian nomads, known as Scythians. The area was incorporated into the Persian Empire and, after a period of Macedonian Greek rule, was ruled mostly by Persian dynasties until the Muslim conquest in the 7th century, turning the majority of the population towards Islam. During this period, cities such as Samarkand, Khiva and Bukhara began to grow rich from the Silk Road.

After the Mongol Conquests, the area became increasingly dominated by Turkic peoples. The city of Shahrisabz was the birthplace of the Turkic warlord Timur, who in the 14th century established the Timurid Empire and was proclaimed the Supreme Emir of Turan with his capital in Samarkand. The area was conquered by Uzbek Shaybanids in the 16th century, moving the centre of power from Samarkand to Bukhara. The region was split into three states: Khanate of Khiva, Khanate of Kokand, and Emirate of Bukhara. It was gradually incorporated into the Russian Empire during the 19th century, with Tashkent becoming the political center of Russian Turkestan. In 1924, after national delimitation, the constituent republic of the Soviet Union known as the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic was created. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, it declared independence as the Republic of Uzbekistan on 31 August 1991.

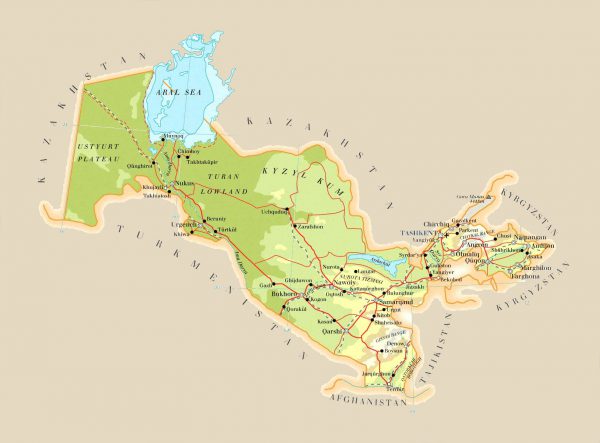

Geography of Uzbekistan

The territory of Uzbekistan is a peculiar combination of flat and steep terrain. The plains are located on the south-west and north-west and consist of Ustyurt, the Amu-Darya delta and the Kyzyl-Kum desert. In central and south-western part of the desert are quite large mountain hill. Mountains and foothills, occupying about a third of the republic, are in the east and south-east, where the interlock with the powerful mountain formations in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The highest point of the mountains of the republic is 4,643 m.

Vegetation patterns in Uzbekistan vary, largely according to altitude. The lowlands in the west have a thin natural cover of desert sedge and grass. The high foothills in the east support grass, and forests and brushwood appear on the hills. Forests cover less than 12 percent of Uzbekistan’s area. Animal life in the deserts and plains includes rodents, foxes, wolves, and occasional gazelles and antelopes. Boars, roe deer bears, wolves, Siberian goats, and some lynx live in the high mountains.

The largest rivers of both Uzbekistan and throughout Central Asia are Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya. The total length of the Amu-Darya River is 1437 km, and Syr-Darya river – 2137 km. Syr-Darya, exceeding Amu-Darya by length, is less by water content.

History of Uzbekistan

In the first millennium BC, Iranian nomads established irrigation systems along the rivers of Central Asia and built towns at Bukhara and Samarqand. These places became extremely wealthy points of transit on what became known as the Silk Road between China and Europe. In the seventh century AD, the Soghdian Iranians, who profited most visibly from this trade, saw their province of Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) overwhelmed by Arabs, who spread Islam throughout the region. Under the Arab Abbasid Caliphate, the eighth and ninth centuries were a golden age of learning and culture in Transoxiana. As Turks began entering the region from the north, they established new states, many of which were Persianate in nature. After a succession of states dominated the region, in the twelfth century, Transoxiana was united in a single state with Iran and the region of Khwarezm, south of the Aral Sea. In the early thirteenth century, that state was invaded by Mongols, led by Genghis Khan. Under his successors, Iranian-speaking communities were displaced from some parts of Central Asia. Under Timur (Tamerlane), Transoxiana began its last cultural flowering, centered in Samarqand. After Timur the state began to split, and by 1510 Uzbek tribes had conquered all of Central Asia.

In the sixteenth century, the Uzbeks established two strong rival khanates, Bukhoro and Khorazm. In this period, the Silk Road cities began to decline as ocean trade flourished. The khanates were isolated by wars with Iran and weakened by attacks from northern nomads. Between 1729 and 1741 all the Khanates were made into vassals by Nader Shah of Persia. In the early nineteenth century, three Uzbek khanates—Bukhoro, Khiva, and Quqon (Kokand)—had a brief period of recovery. However, in the mid-nineteenth century Russia, attracted to the region’s commercial potential and especially to its cotton, began the full military conquest of Central Asia. By 1876 Russia had incorporated all three khanates (hence all of present-day Uzbekistan) into its empire, granting the khanates limited autonomy. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Russian population of Uzbekistan grew and some industrialization occurred.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Jadidist movement of educated Central Asians, centered in present-day Uzbekistan, began to advocate overthrowing Russian rule. In 1916 violent opposition broke out in Uzbekistan and elsewhere, in response to the conscription of Central Asians into the Russian army fighting World War I. When the tsar was overthrown in 1917, Jadidists established a short-lived autonomous state at Quqon. After the Bolshevik Party gained power in Moscow, the Jadidists split between supporters of Russian communism and supporters of a widespread uprising that became known as the Basmachi Rebellion. As that revolt was being crushed in the early 1920s, local communist leaders such as Faizulla Khojayev gained power in Uzbekistan. In 1924 the Soviet Union established the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, which included present-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Tajikistan became the separate Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic in 1929. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, large-scale agricultural collectivization resulted in widespread famine in Central Asia. In the late 1930s, Khojayev and the entire leadership of the Uzbek Republic were purged and executed by Soviet leader Joseph V. Stalin (in power 1927–53) and replaced by Russian officials. The Russification of political and economic life in Uzbekistan that began in the 1930s continued through the 1970s. During World War II, Stalin exiled entire national groups from the Caucasus and the Crimea to Uzbekistan to prevent “subversive” activity against the war effort.

Moscow’s control over Uzbekistan weakened in the 1970s as Uzbek party leader Sharaf Rashidov brought many cronies and relatives into positions of power. In the mid-1980s, Moscow attempted to regain control by again purging the entire Uzbek party leadership. However, this move increased Uzbek nationalism, which had long resented Soviet policies such as the imposition of cotton monoculture and the suppression of Islamic traditions. In the late 1980s, the liberalized atmosphere of the Soviet Union under Mikhail S. Gorbachev (in power 1985–91) fostered political opposition groups and open (albeit limited) opposition to Soviet policy in Uzbekistan. In 1989 a series of violent ethnic clashes involving Uzbeks brought the appointment of ethnic Uzbek outsider Islam Karimov as Communist Party chief. When the Supreme Soviet of Uzbekistan reluctantly approved independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Karimov became president of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

In 1992 Uzbekistan adopted a new constitution, but the main opposition party, Birlik, was banned, and a pattern of media suppression began. In 1995 a national referendum extended Karimov’s term of office from 1997 to 2000. A series of violent incidents in eastern Uzbekistan in 1998 and 1999 intensified government activity against Islamic extremist groups, other forms of opposition, and minorities. In 2000 Karimov was reelected overwhelmingly in an election whose procedures received international criticism. Later that year, Uzbekistan began laying mines along the Tajikistan border, creating a serious new regional issue and intensifying Uzbekistan’s image as a regional hegemon. In the early 2000s, tensions also developed with neighboring states Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan. In the mid-2000s, a mutual defense treaty substantially enhanced relations between Russia and Uzbekistan. Tension with Kyrgyzstan increased in 2006 when Uzbekistan demanded extradition of hundreds of refugees who had fled from Andijon into Kyrgyzstan after the riots. A series of border incidents also inflamed tensions with neighboring Tajikistan. In 2006 Karimov continued arbitrary dismissals and shifts of subordinates in the government, including one deputy prime minister.

Culture of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan`s culture has been formed over millenniums and has taken in traditions of various nations settled on the territory of today Uzbekistan.

The main contribution to the development was made by ancient Iranians, nomad Turkic tribes, Arabs, Chinese, Russians. Traditions of multinational Uzbekistan reflected in the music, dances, fine art, applied arts, language, cuisine and clothing. Population of the republic, especially rural population revere traditions deeply rooted in the history of the country.

The Great Silk Road played a great role in the development of Uzbekistan culture. Being the trade route, it ran from China to two destinations: first one was to Ferghana Valley and Kazakh steppes and second route led to Bactria, and then to Parthia, India and Middle East up to Mediterranean Sea. The Silk Road favored to exchange not only goods, but also technologies, languages, ideas, religions. Thereby the Great Silk Road led to the spread of Buddhism on the territory of Central Asia, where you still may find traces of Buddhist culture: Adjina-tepe in Tadjikistan, Buddhist temple in Kuva, Ferghana valley, Fayaz-Tepa near Termez in Uzbekistan and etc.

Afrasiyab

Afrasiyab (Afrosiyob) is an ancient site of northern Samarkand which was occupied from 500 BC to 1220 AD. Today it is a hilly grass mound located near the Bibi Khanaum Mosque.

Afrasiyab is the oldest part and the ruined site of the ancient and medieval city of Samarkand. It was located on high ground for defensive reasons, south of a river valley and north of a large fertile area which has now became part of the city of Samarkand.

The habitation of the territories of Afrasiyab began in the 7th-6th century BC, as the centre of the Sogdian culture.

The area of Afrasiyab covers about 220 hectares, and the thickness of the archaeological strata reaches 8–12 metres. Archaeological excavations have been carried out in Afrasiyab since the end of the 19th century. In the 1920s it was extensively excavated by the archaeologist Mikhail Evgenievich Masson who placed artifacts found at the site in the Samarkand museum. His archaeological study revealed that a Samanid palace had once been located at Afrasiyab. It was again actively excavated during the 1960-70s.

Bibi-Khanym Mosque

Bibi-Khanym Mosque is a famous historical mosque in Samarkand, the name comes from the wife of 14th-century ruler, Amir Timur.

After his Indian campaign in 1399 Timur decided to undertake the construction of a gigantic mosque in his new capital, Samarkand. The mosque was built using precious stones captured during his conquest of India. According to Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo, 90 captured elephants were employed merely to carry precious stones, so as to erect a mosque at Samarkand — Bibi-Khanym Mosque. Construction was completed between 1399 and 1404. However, the mosque slowly fell into disuse, and crumbled to ruins over the centuries. Its demise was hastened due to the fact it pushed the construction techniques of the time to the very limit, and the fact that it was built too quickly. It eventually partially collapsed in 1897 when an earthquake occurred.

However, in 1974 it began to undergo reconstruction by the Government of Uzbekistan. The bazaar at thefoot of the Bibi-Khanym has changed little since 600 years ago.

Gur-e Amir

Gur-e Amir is Persian for “Tomb of the King”. This architectural complex with its azure dome contains the tombs of Tamerlane, his sons Shah Rukh and Miran Shah and grandson Ulugh Beg and Muhammad Sultan. Also honoured with a place in the tomb is Timur’s teacher Sayyid Baraka.

The earliest part of the complex was built at the end of the 14th century by the orders of Muhammad Sultan. Now only the foundations of the madrasah and khanaka, the entrance portal and a part of one of four minarets remain.

The construction of the mausoleum itself began in 1403 after the sudden death of Muhammad Sultan,Tamerlane’s heir apparent and his beloved grandson, for whom it was intended. Timur had built himself a smaller tomb in Shahrisabz near his Ak-Saray palace. However, when Timur died in 1405 on campaign on his military expedition to China, the passes to Shahrisabz were snowed in, so he was buried here instead. Ulugh Beg, another grandson of Tamerlane, completed the work. During his reign the mausoleum became the family crypt of the Timurid Dynasty.

Registan

The Registan was the heart of the ancient Samarkand. The name Registan means “Sandy place” in Persian.

The Registan was a place of public executions, where also people gathered to hear royal proclamations, heralded by blasts on enormous copper pipes called dzharchis.

The three madrasahs of the Registan are: Ulugh Beg Madrasah (1417–1420), Tilya-Kori Madrasah (1646–1660) and the Sher-Dor Madrasah (1619–1636). Madrasah is an Arabic term meaning school.

Ulugh Beg Madrasah

The Ulugh Beg Madrasah has its imposing portal with lancet arch facing the square. The corners are flanked by the high well-proportioned minarets. Mosaic panel over the entrance arch is decorated by geometrical stylized ornaments. The square-shaped courtyard includes a mosque, lecture rooms and is fringed by the dormitory cells in which students lived. There are deep galleries along the axes. Originally the Ulugh Beg Madrasah was a two-storied building with four domed darskhonas (lecture room) at the corners. The madrasah was one of the best clergy universities of the whole Moslem Orient of the 15th century. Abdurakhman Djami, a prominent poet, scientist and philosopher studied there. Ulugh Beg himself gave lectures there. During Ulugh Beg’s government the madrasah was a center of secular science.

Sher-Dor Madrasah.

In the 17th century the ruler of Samarkand Yalangtush Bakhodur ordered the construction of the Sher-Dor and Tillya-Kori madrasahs. Sher-Dor (Having Tigers) Madrasah was designed by architect Abdujabor. The decoration of the madrasah is not as refined as that on the 15th century – “golden age” of Samarkand architecture. Anyway, the harmony of large and small rooms, exquisite mosaic decor, monumentality and efficient symmetry – all these put the structure among the best architectural monuments of Samarkand.

Tilya-Kori Madrasah

Ten years later Tilya-Kori Madrasah was built, the name means “Gilded”. It was not only the place of training students, but also it played the role of grand mosque. It has two-storied main facade, vast courtyard fringed by dormitory cells with four galleries along axes. Mosque building is situated in the western section of the courtyard. The main hall of the mosque is abundantly gilded.

Chorsu

The ancient trading dome Chorsu is situated right behind the Sher-Dor Madrasah. Now it is well restored. The existence of the trading dome at this place confirms the information that Registan was medieval Samarkand’s commercial center and the plaza was probably a wall to wall market. During the Soviet epoch, the site was restored, which included digging down 3 meters to its original level to expose the buildings’ full height.

Samarkand

Samarkand (from Sogdian: “Stone Fort” or “Rock Town”) is the second-largest city in Uzbekistan and the capital of Samarqand Province. The city is most noted for its central position on the Silk Road between China and the West, and for being an Islamic center for scholarly study. In the 14th century, it became the capital of the empire of Timur (Tamerlane), and is the site of his mausoleum (the Gur-e Amir). The Bibi-Khanym Mosque remains one of the city’s most notable landmarks. The Registan was the ancient center of the city.

Shah-i-Zinda

Shah-i-Zinda (Persian meaning “The Living King”) is a necropolis in the north-eastern part of Samarkand.

The Shah-i-Zinda Ensemble includes mausoleums and other ritual buildings of 9-14th and 19th centuries. The name Shah-i-Zinda is connected with the legend that Kusam ibn Abbas, the cousin of the prophet Muhammad was buried there. As if he came to Samarkand with the Arab invasion in the 7th century to preach Islam. Popular legends tell that he was beheaded for his faith. But he took his head and went into the deep well (Garden of Paradise), where he’s still living now.

The Shah-i-Zinda complex was formed over nine (from 11th till 19th) centuries and now includes more than twenty buildings.

Ulugh Beg observatory

In 1420, the great astronomer Ulugh Beg built a madrasah in Samarkand, named Ulugh Beg Madrasah. It became an important center for astronomical study and only invited scholars to study at the university whom he personally approved of and respected academically and at its peak had between 60 and 70 astronomers working there. In 1424, he began building the observatory to support the astronomical study at the madrasah and it was completed five years later in 1429. Beg assigned his assistant and scholar Ali Qushji to take charge of the Ulugh Beg Observatory, which was called Samarkand Observatory at that time. He worked there till Ulugh Beg was assassinated.

However, the observatory was destroyed by religious fanatics in 1449 and was only re-discovered in 1908, by Uzbek-Russian archaeologist from Samarkand named V. L. Vyatkin, who discovered an endowment document that stated the observatory’s exact location.

Bukhara

Bukhara from the Soghdian βuxārak (“lucky place”), is the capital of the Bukhara Province (viloyat) of Uzbekistan. The nation’s fifth-largest city, it has a population of 263,400 (2009 census estimate). The region around Bukhara has been inhabited for at least five millennia, and the city has existed for half that time. Located on the Silk Road, the city has long been a center of trade, scholarship, culture, and religion. The historic center of Bukhara, which contains numerous mosques and madrassas, has been listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Ethnic Tajiks (Persians) constitute the majority in Bukhara, but the city long had a population including various ethnic minoritie.

Po-i-Kalan

The title Po-i Kalan (Persian meaning the “Grand Foundation”), belongs to the architectural complex located at the base of the great minaret Kalân.

Kalyan minaret. More properly, Minâra-i Kalân, (Pesian/Tajik for the “Grand Minaret”). It is made in the form of a circular-pillar brick tower, narrowing upwards, of 9 meters (29.53 ft) diameter at the bottom, 6 meters (19.69 ft) overhead and 45.6 meters (149.61 ft) high. Also, known as the Tower of Death, as for centuries criminals were executed by being tossed off the top.

Kalân Mosque (Masjid-i Kalân), arguably completed in 1514, is equal to the Bibi-Khanym Mosque in Samarkand in size. Although, they are of the same type of building, they are absolutely different in terms of art of building.

Mir-i Arab

There is little known about its origin, although its construction is ascribed to Sheikh Abdullah Yamani of Yemen, the spiritual mentor of early Shaybanids. He was in charge of donations of Ubaidollah Khan (gov. 1533-1539), devoted to construction of madrasah.

Ismail Samani mausoleum

Ismail Samani mausoleum (9th-10th century), one of the most esteemed sights of Central Asian architecture, was built in the 9th century (between 892 and 943) as the resting-place of Ismail Samani – the founder of the Samanid dynasty, the last Persian dynasty to rule in Central Asia, which held the city in the 9th and 10th centuries. Although in the first instance the Samanids were Governors of Khorasan and Ma wara’u’n-nahr under the suzerainty of the Abbasid Caliphate, the dynasty soon established virtual independence from Baghdad.

Chashma-Ayub mausoleum

Chashma-Ayub is located near the Samani mausoleum. Its name in Persian means Job’s spring due to the legend according to which Job (Ayub) visited this place and brought forth a spring of water by the blow of his staff on the ground. The water from this well is still pure and is considered healing. The current building was constructed during the reign of Timur and features a Khwarazm-style conical dome uncommon in Bukhara.

Lab-i Hauz

Lab-i Hauz (Persian meaning by the pond) Ensemble (1568–1622) is the name of the area surrounding one of the few remaining hauz (ponds) in the city of Bukhara. Until the Soviet period there were many such ponds, which were the city’s principal source of water, but they were notorious for spreading disease and were mostly filled in during the 1920s and 1930s. The Lyab-i Hauz survived because it is the centerpiece of a magnificent architectural ensemble, created during the 16th and 17th centuries, which has not been significantly changed since. The Lyab-i Hauz ensemble, surrounding the pond on three sides, consists of the Kukeldash Madrasah (1568–1569), the largest in the city (on the north side of the pond), and of two religious edifices built by Nadir Divan-Beghi: a khanaka (1620), or lodging-house for itinerant Sufis, and a madrasah (1622) that stand on the west and east sides of the pond respectively.

Tashkent

At the moment, it is the most cosmopolitan city in Uzbekistan, with large ethnic Russian minority. The city is noted for its tree lined streets, numerous fountains, and pleasant parks.

Since 1991, the city has changed economically, culturally, and architecturally. The largest statue ever erected for Lenin was replaced with a globe, complete with a geographic map of Uzbekistan over it. Buildings from the Soviet era have been replaced with new, modern buildings. One example is the “Downtown Tashkent” region, which includes the 22-storey NBU Bank building, an Intercontinental Hotel, International Business Center, and the Plaza Building.

In 2007, Tashkent was named the cultural capital of the Islamic world as the city is home to numerous historic mosques and religious establishments. Tashkent also houses the earliest written Qur’an, which has been in Tashkent since 1924.

Due to the destruction of most of the ancient city during 1917 revolution and, later, to the 1966 earthquake, little remains of Tashkent’s traditional architectural heritage. Tashkent is, however, rich in museums and Soviet-era monuments. They include:

• Kukeldash Madrasah. Dating back to the reign of Abdullah Khan (1557–1598) it is currently being restored by the provincial Religious Board of Mawarannahr Moslems. There is a talk of making it into a museum, but it is currently being used as a mosque.

• Chorsu Bazaar, located near the Kukeldash Madrassa. This huge open air bazaar is the center of the old town of Tashkent. Everything imaginable is for sale.

• Telyashayakh Mosque (Khast Imam Mosque). It contains the Uthman Qur’an, considered to be the oldest extant Qur’an in the world. Dating from 655 and stained with the blood of murdered caliph, Uthman, it was brought by Timur to Samarkand, seized by the Russians as a war trophy and taken to Saint Petersburg. It was returned to Uzbekistan in 1924.

• Yunus Khan Mausoleum. It is a group of three 15th century mausoleums, restored in the 19th century. The biggest is the grave of Yunus Khan, grandfather of Mughal Empire founder Babur.

• Palace of Prince Romanov. During the 19th century Grand Duke Nikolai Konstantinovich, a first cousin of Alexander III of Russia was banished to Tashkent for some shady deals involving the Russian Crown Jewels. His palace still survives in the centre of the city. Once a museum, it has been appropriated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

• Alisher Navoi Opera and Ballet Theatre, built by the same architect who designed Lenin’s Tomb in Moscow, Aleksey Shchusev, with Japanese prisoner of war labor in World War II. It hosts Russian ballet and opera.

• Fine Arts Museum of Uzbekistan. It contains a major collection of art from the pre-Russian period, including Sogdian murals, Buddhist statues and Zoroastrian art, along with a more modern collection of 19th and 20th century applied art, such as suzani embroidered hangings. Of more interest is the large collection of paintings “borrowed” from the Hermitage by Grand Duke Romanov to decorate his palace in exile in Tashkent, and never returned. Behind the museum is a small park, containing the neglected graves of the Bolsheviks who died in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and to Ossipov’s treachery in 1919, along with first Uzbekistani President Yuldosh Akhunbabayev.

• Museum of Applied Arts. Housed in a traditional house originally commissioned for a wealthy tsarist diplomat, the house itself is the main attraction, rather than its collection of 19th and 20th century applied arts.

• History Museum the largest museum in the city. It is housed in the ex-Lenin Museum.

• Amir Timur Museum, housed in a building with brilliant blue dome and ornate interior. It houses exhibits of Timur and of President Islam Karimov. The gardens outside contain a statue of Timur on horseback, surrounded by some of the nicest gardens and fountains in the city.

• Navoi Literary Museum, commemorating Uzbekistan’s adopted literary hero, Alisher Navoi, with replica manuscripts, Persian calligraphy and 15th century miniature paintings.

Khiva

Khiva is a city of approximately 50,000 people located in Xorazm Province, Uzbekistan. It is the former capital of Khwarezmia and the Khanate of Khiva. Itchan Kala in Khiva was the first site in Uzbekistan to be inscribed in the World Heritage List (1991). Khiva is split into two parts. The outer town, called Dichan Kala, was formerly protected by a wall with 11 gates. The inner town, or Itchan Kala, is encircled by brick walls, whose foundations are believed to have been laid in the 10th century. Present-day crenellated walls date back to the late 17th century and attain the height of 10 meters. The large blue tower in the central city square was supposed to be a minaret, but the Khan died and the succeeding Khan did not complete it, perhaps because he realized that if completed, the minaret would overlook his harem and the muezzin would be able to see the Khan’s wives. Construction was halted and the minaret remains unfinished to this day.

The old town retains more than 50 historic monuments and 250 old houses, mostly dating from the 18th or the 19th centuries. Djuma Mosque, for instance, was established in the 10th century and rebuilt in 1788-89, although its celebrated hypostyle hall still retains 112 columns taken from ancient structures.

It also is the site of the Sheikh Mukhtar-Vali Complex, a mausoleum nominated for World Heritage status in 1996.

Destinations

Find more information about the countries on the Great Silk Road

Русский

Русский Español

Español Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch